Since she was a kid, Ana Patricia Ponce Castañeda has loved horror films and fondly remembers watching scary movies with her mom as she was growing up in Mexico.

Now, a second-year Ph.D. student in the Hispanic Cultural Studies program at Michigan State University, Castañeda has found a way to merge her childhood love of horror with her adult interests in film, popular culture, and gender studies.

“Horror has always been a way for me to make sense of the world, not just now that I use it to analyze culture and gender,” she said. “We use it to explore the things we are afraid of and try to make sense of how you feel, and what we think of things.”

Castañeda’s research for her dissertation focuses on female representation in Latin American horror cinema.

“Hispanic cinema is very rich and is worth watching,” she said. “It is a really important part of World Cinema and is helping people make sense of their own culture and their own socio-political situation.”

“Horror has always been a way for me to make sense of the world…We use it to explore the things we are afraid of and try to make sense of how you feel, and what we think of things.”

Castañeda traveled to Mexico on a 2023 summer fellowship through the Center for Latin American and Caribbean Studies (CLACS) to conduct research for her dissertation at the National Cinema Theater (Cineteca Nacional).

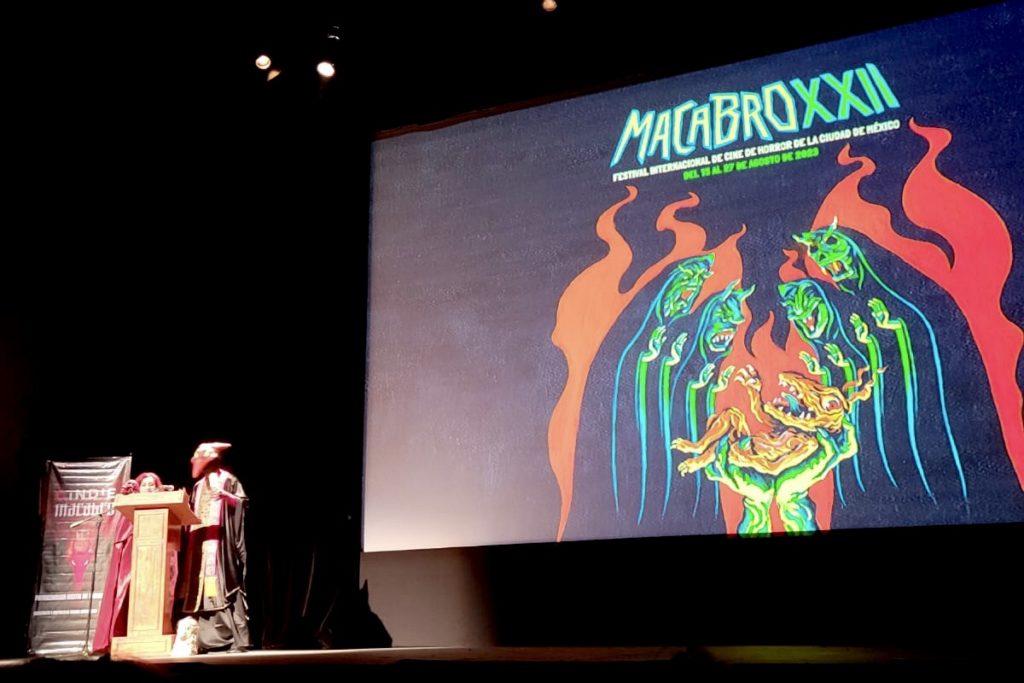

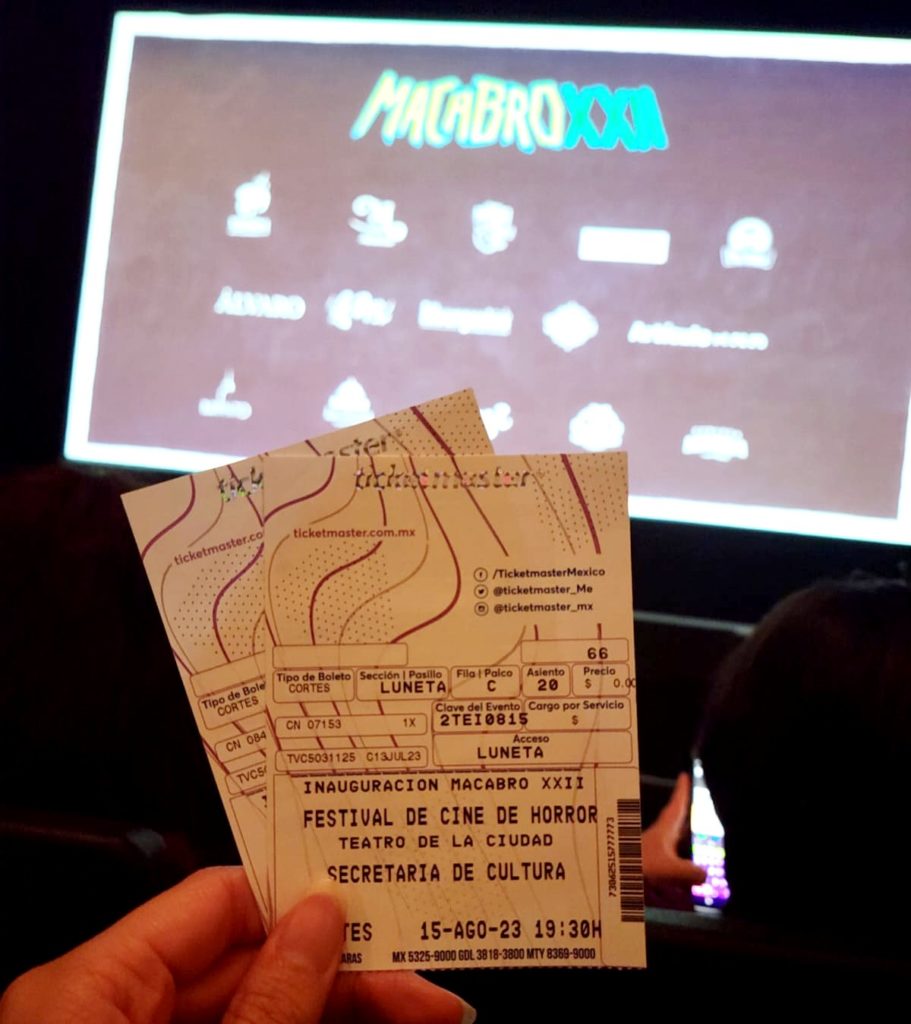

The fellowship allowed Castañeda to stay in Mexico City for a month where she combed through the National Cinema Theater archives, reading articles and dissertations and watching the films that were discussed. She also went to the annual Macabro: Film and Video Horror Festival where she attended premiers for many feature and short films.

“My time in Mexico City for the fellowship was really useful, because maybe you can access some of the movies on the internet, but it’s the archive that is really the important part,” she said. “I had access to journal articles, magazine articles, newspaper articles, and also dissertations about cinema and horror cinema. Some of them were about women in horror cinema and, for some, you’re not able to get that on the internet.”

For her dissertation, Castañeda studied 13 Mexican horror films spanning from 1934 to 2023, analyzing how women are portrayed in each film in terms of the roles they play and how they visually appear on screen. In doing this, she created a three-part film analysis instrument that focuses on the semiotic, aesthetic, and cultural aspects of each film.

“Hispanic cinema is very rich and is worth watching. It is a really important part of World Cinema and is helping people make sense of their own culture and their own socio-political situation.”

She found that the way women are visually portrayed in horror cinema has changed with time. For example, in the past, there was a heavy emphasis on making women look desirable on screen, even in the context of a horror movie. Cameras were placed in such a way to shoot women at flattering angles and to accentuate their sexuality.

“Especially in early cinema, you can find these shots where it’s a really close-up frame of the female body, or body parts, or a full shot with the camera movement scanning all of the female’s body,” she said. “It’s a little bit stereotypical, objectifying, or sexist.”

According to Castañeda, the industry is now moving away from using women’s sexuality in a way to bring pleasure to the viewer when it does not advance the plot.

Castañeda also found, especially in the first half of horror cinema history, that women often played the role of the victim or casualty, suffering damage for the things that men do within the narrative.

“I think it’s a little bit of a strategy to attract viewers, but also to say that women are these people who need to be protected, or who are fragile, or are in danger all of the time,” she said. “But in Mexican cinema, this is the first thing that started to change.”

According to Castañeda, it took longer for the narratives to change, with many of the films that featured women in an agency role about seduction at the hands of a villainous woman, or a witch corrupting an innocent woman. This change took longer to manifest in Mexican horror cinema than in Hollywood horror according to Castañeda, but it really took off in both after the height of the #MeToo movement in 2017.

“In early horror cinema, with how the monsters are depicted on screen, you can see how it’s always a metaphor for a minority group. And you can trace every monster into these types of narratives.”

This is a natural progression, Castañeda says, since the horror genre plays upon people’s fears, often utilizing stereotypes to target or point out widespread societal misconceptions and generate fear in the viewer.

“In early horror cinema, with how the monsters are depicted on screen, you can see how it’s always a metaphor for a minority group,” she said. “And you can trace every monster into these types of narratives, but it’s been progressing a bit.”

Now big cinema is starting to change the way audiences see monsters, using them to portray political-based fears, representing what they are worried about more so than who they are worried about using gender- or race-related stereotypes.

Castañeda said that female-gendered monsters often represent the things that society fears from modern women, touching on themes of social, sexual, economic, and political liberation.

“Now it’s more about telling the story of the things that we should fear in reality, so for example, in Mexico it’s violence against women,” she said. “In horror, the monster figure is very important because it’s the foundation for horror, but it’s also a door to open the conversation about the things that are happening in reality.”

However, horror movies have always been very linked to violence, Castañeda says.

“In horror, the monster figure is very important because it’s the foundation for horror, but it’s also a door to open the conversation about the things that are happening in reality.”

“In early movies, you can find some scenes that can be very violent, and very explicit,” she said. “But the latest movies try to show violence in a way that’s not gore cinema by not showing it so explicitly. So how to show women’s sexuality and violence against women and women’s desires and fears, but not make it morbid and rather make it a natural conversation that revolves around fear. In the end, it’s a horror movie and is supposed to scare you, but it’s also supposed to visually show and make people understand what is happening in the world.”

With Mexican horror cinema, it also has always been concerned with witchcraft, Castañeda says, but not in the European sense of it.

“It’s a very distinctive type of witchcraft based on indigenous people’s vision of the world, how they make sense of the world through mythological tales, but it’s also the combination of that with the Catholicism that was brought to America during the colony,” Castañeda said. “In Mexican cinema, the mix of these two cultures is very visible.”

According to Castañeda many of the narratives in Mexican horror involving women usually center around women’s communication, relationships with each other, motherhood, and experiencing violence.

“It’s always about how women have a relationship with each other,” she said. “And in early cinema, it’s a little bit about how that can be dangerous. And as time progresses, it’s more about how women can help each other. So, I think, you could say that Mexican culture is very concerned about how women interact with each other. But it also shows a shift in perspective because right now it’s more about how women can help each other and achieve these networks to help each other.”

Castañeda plans to complete her dissertation in 2026 and graduate with her Ph.D. in 2027. She then hopes to continue working on academia in the fields of Latin American Studies, Film Studies, and Gender Studies.